CYPRUS - PHANOS KYRIACOU

Suddenly Emergent

Modernism, that discriminating appropriation of the conditions of alteration heralded by the prolonged period of the modern, has established itself mostly via its architecture rather than its revolutions. In a Gothic chapel in the castle La Sarraz, a few miles north of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, under the auspices, and indeed after a direct commission from Mme Helene de Mandot, Sigfried Gideon and Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, aka Le Corbusier, appended to by two dozen others, canonised a manifesto and an association that still dominates our understanding of modernity. True nonetheless to the modality of revolutions, this first manifesto of CIAM emphatically stated as an aim the affirmation of “a unity of viewpoint on the fundamental conceptions”, of its discipline, namely architecture. As with any purging orthodoxy, the proclaimed modernism of CIAM defined the divides with its past but also within itself, thus activating the rifts from where an other tradition was to mobilise the same historical and material conditions for. Against the systematic standardisation of the building as object, later defended as The International Style, a view of the build environment as “a framework for the actions of men, a race of enactment and celebration, a theatre that makes action possible”1 was diffused giving rise to numerous local modernisms. Against mimesis, methexis.

This transformative opening up of architecture as a critical, reflective act, in the context of its particular relations of production, rather than a regimented technological outcome, formed much of the local idiom of architectural modernism of Cyprus. The utilisation of vernacular methods and materials like the porous, dark-yellow limestone by Polys Michaelides either as load bearing material in his Bauhaus influenced designs for the Nicosia Orphanage building (1934) and the now demolished General Hospital (1939) or later as facade cladding, the use of sea pebbles by Charilaos Dikaios and Neoptolemos Michaelides in their mid-1940's concrete structures, and the later's attempts to incorporate adobe bricks in high-rises, are but a few examples of early re-arrangements of materials and techniques within the modernist tradition, rather than its mere stylistic adaptation. Such arrangements apart from setting up an active but critical relationship with the ideals of modernism, became, as any arrangement, a means of circulation, of transmission of these new conditions for architecture, uninterrupted by the complexities of technological or other fidelity.

As a consequence newly imported materials and designs such as concrete, corrugated iron, aluminium and facilities for domestic sanitation were and still are thoroughly and unapologetically utilised en masse, beyond the formalised design. The city, the buildings, architectural modernism, is thus to be found redistributed not as remodelings of macro strategies but in “in a continual process of discontinuous transformation”.2

These discontinuous redistributions of knowledge and information, at the core of the project of modernity, have often been lost between glorified pageants of the favela-chic, the idealised accounts of ingenuity in a recent revengeful return of place and the resistant obedience of the specialist terming them as surplus, useless to its hagiographic historiography. This intricate transformation of urban and architectural experience however reveal the incomplete process of modernity by negotiating its formal limits allowing for a critical spatial practise to emerge. Critical spatial culture denotes a transformative rather than descriptive engagement with the varieties of disciplines and issues operating diagonally across 3 the conventional occupations and enactments of space.4 Latent in critical spatial culture has always been a resilient transgression, the indisciplined 5 affairs of art in and out of its outgrown boundaries.

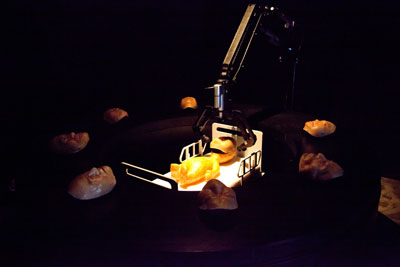

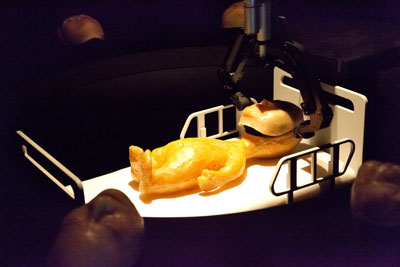

Phanos Kyriacou, an artist employing simultaneously the sensibilities and practises of an ikebana arrange and of a punk film-maker, is one of the main Cypriot perpetrators of this transgressive relationships of art. Phanos Kyriacou's practise is retrieved from the outskirts of craftmanship, obsessive research and civic engagement. With his idiosyncratic, Daedalic humour he is acutely aware of the intricacies of materials embedded in locations and structure. It is this attentiveness that persists in his varied output and which configures his re-arrangements of the factual, the historical. From objects to posters and from paintings to landscapes Kyriacou interstices our perception of space, problematising the notion of location, often via the already problematic local. His investigation into the forgotten, lost mountainous regions of the island (Wonder Chambers, 2007) have dispersed into his fragmented almost illegible portraits of shamans and visionaries, devoid of their iconographical status and devotional characteristics of The Visionaries series. His photographic and performative explorations of scenery and topography (A majestic escape from a parasitic society, 2006-2007) become odd, unreal landscapes, of tall and thin sculptures beyond the primacy of the real, escapees from geographical signification. His oscillations to and for the backstage of history, as is his recurring preoccupation with Bruno Taut (see for example the intricate Problem Solved, 2010 or Bruno Taut's mountain cave, 2009) or print works under the Midget Factory nom de plume, expose the cracks of monumentality and remembrance, underlined in the My heroes series of works and most evident, not least through their boulder-like materiality, in Phanos Kyriacou's most recent sculptures, including They had to climb a minor hill in order to enjoy a full view of their problem, 2010.

Phanos Kyriacou's work inflates space, expanding our grasp of its particulars over and above the demolishing silences of history and its monolithic orthodoxies. From the ridgelines of an uninhibited art and an indisciplined architecture he rigorously transcribes, re-arranges, the anexact 6 privateerings that continuously open up the in-finite conditions of possibility of the emergent in all its discontinuous disparities with the illustrations of programmatic predictabilities.

1 Colin St John Wilson, 2007, p. 86

2 Howard Caygill, 1998, p. 121

3 On the interdisciplinary and the diagonal see Julia Kristeva, 'Institutional interdisciplinarity in theory and practice: an interview' IN Alex Coles and Alexia Defert (Eds), 1998, The Anxiety of Interdisciplinarity, De-, Dis-, Ex-, Vol. 2, Black Dog Publishing, London

4 See Rendell, 2006, pp. 3-12

5 More on the indisciplined in the indisciplinary see W.J.T. Mitchell 'Interdisciplinarity and Visual Culture' IN Art Bulletin, 77/4 December 1995

6 “Husserl speaks of a protogeometry that addresses vague, in other words, vagabond or nomadic. Morphological essences. These essences are distinct from sensible things, as well as from ideal, royal or imperial essence. Protogeometry, the science dealing with them, is itself vague, in the etymological sense of 'vagabond': it is neither inexact like sensible things nor exact like ideal essences but anexact yet rigorous ('essentially and not accidentally inexact'). The circle is an organic, ideal, fixed essence, but roundness a vague and fluent essence, distinct from both the circle and things that are round (a vase, a wheel, the sun). A theorimatic figure is a fixed essence but its transformations, distortions, ablations, and augmentations, all of its variations, form problematic figures that are vague yet rigorous, 'lens-shaped', 'umbeliform', or 'indented'. It could be said that vague essences extract from things a determination that is more than thinghood, which is that of corporeality and which perhaps even implies an esprit de corps.” Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, Athlone Press, 1999, p. 367

For an extended discussion on anexact geometry and its implications with materiality in the spatial field see Reiser and Unemoto, Atlas of Novel Tectonics, Princeton Architectural Press, 2006, pp. 144-149.

Text by Demetris Taliotis

CHINA – YI ZHOU

In her latest 3-D animation video The Greatness, multimedia artist Zhou Yi takes the viewer to hell and back. Using visual references from her previous works inspired by Dante’s The Divine Comedy and featuring samples of unpublished tracks and melodies from the archives of Italian composer Ennio Morricone, the atmospheric new work is both beautiful and haunting.

“I wanted to reproduce a dream or a nightmare sequence. The soundtrack also helps to enhance the message I want to deliver… the kind of feeling, which is going to hell and then back, so that was the idea” the 31-year-old artist says.

The Greatness is part of Zhou’s ongoing investigation into the themes of death and the afterlife, topics that are considered taboo among the Chinese. She believes that only by confronting the unknown can the fear of the inevitable be overcome.

Zhou began creating a series of video installations and sculptures five years ago, based on her interpretations of paradise, purgatory and inferno. What drew the artist to Dante’s masterpiece – written in the early 14th century about a man’s journey from hell to paradise – is not only the poetic writing by the universality of its themes.

Zhou says she is fascinated by “the idea of death, the idea of fear and the idea of how we imagine our lives after death” because they are fertile ground for her imagination.

French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s Apories, a book she had reread in the past year, fuelled her interest, especially the fear of death: “It describes the idea of death and… when we think about that motion, the idea of why we are scared of that.

It seems to be an obstacle japory stems from the Greek word aporia, which means difficult because it is something that we’ve never faced so we don’t know what it is and the fact that it is an unknown factor… increases the fear because nobody can ever describe to use how it is.

So when I read the book, it helped me to… have less fear about that idea, which is more of a human construction of that idea of death. If you look at it in a different way, to look at it in a different way, to look at it as a boundary between two spheres, [death is when] you walk pass this boundary.”

Text by Kevin Kwong

CHINA, HONG KONG - AMY CHEUNG

"Like a person without a face, reason cannot tolerate the representation of its own mirror image."

Slavok Zizek & John Mibank

Inspired by John Woo films’ signature action sequences, the glamorous violence, the choreographed violence, the justified violence, the purposeful violence… Should violence gunned by the hands of a morally incorruptible protagonist be justified as good violence? Can moral integrity pay a role in constructive destruction? How can we distinguish good violence from bad? Won’t we lose the proper instrumental use of the division by our innate ideological orientation and education? As soon as we claim to be developing criteria by which to define a supposedly good violence, each of us will find it easier to make excuses and causes of justice in order to validate our own acts of violence. Therefore, I shall use this opportunity to collect and uncover the climatic discourses of public’s conscientious good and bad violence, through documenting the public’s face mask and a short comment.

Text by the Artist

ARGENTINA - NORA INIESTA

The work of Nora Iniesta escapes from definitions. The diversity of techniques that she dominates allows her to use elements of everyday life and create in its combination a new meaning to the objects she uses.

An umbrella tells us always about the need of protection. In Venice she remembers its beach, the Lido, and its intense heat. To the cinema’s lovers, she evokes Luchino Visconti and its unforgettable Death in Venice, Silvana Mangano dominating elegantly the umbrella and the well-known festival that every year joins the most important of the international cinema.

For the use of the laces that repeat the colours of our country’s national emblem, they give a special symbolic value and turns the object into a sign of union between the culture of both nations. Argentine culture nourishes itself from original elements and those brought by the immigrations from different places of the world. Italy was one of the most important ones in number and influence. Argentine was multicultural when the world was not yet such and the tracks left by Italy in its expressions are thorough and tangible.

This umbrella made up of Argentine laces, tells us about its union between both cultures and the protection that it brings us, in the continuous dialogue that exists between both countries. Nevertheless, as the whole work of Nora Iniesta, the reaffirmation of images and objects with which it nourishes itself challenges the spectator to contemplate with its glance the utter sense of its composition. The artist also recovers the idea of art as an ingenuous game and that is why she proposes an active participation, so that the meeting with an element of everyday use, utterly taken from reality, may get the sense that she proposes and that the watchers end up. As an authentic representative of contemporary art, she uses her creative freedom by the use of various techniques and the desacralization of the things she uses.

As Jacques Derrida says, Iniesta always is in the search of an identity that is never given or granted, for it always flows in the endless process, the indefinitely ghost of identity.

Text by Josè Miguel Onaindia